The Lateral Raphe, Quadratus Lumborum and the 2023 FSOMA conference

I will be presenting about the lateral raphe and the quadratus lumborum at the 2023 Florida State Oriental Medical Association )FSOMA) annual conference on Aug. 27. Details are available here. This post and the video below will give a preview of a portion of this presentation. I hope to see you there!

The Lateral Raphe and Low Back Health

Many manual therapists use high velocity low amplitude (HVLA) adjustments (such as a chiropractic or osteopathic adjustment) to move the body frame and reposition joints. I follow more of the structural integration model where I use the fascia as a lever to move and mobilize the body's skeletal framework. The lateral raphe of the low back is one of these important levers that can influence so much of the low back that it is important to understand the anatomy and use this understanding to better mobilize and move the body.

|

| Netter Image showing TLF |

The lateral raphe is part of the larger thoracolumbar fascia (TLF). The TLF is the diamond shape aponeurosis (wide, flat tendon) seen in musculature illustration of the back. These illustrations don't do it justice since this isn't simply a single layer structure, but is, instead, a multilayer fascial structure with attachments to so many prominent structures of the low back.

|

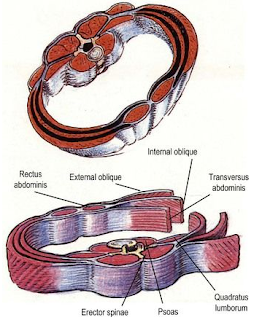

| From Human Structure and Shape by John Hull Grundy |

The fascia from the abdominal muscles, primarily the internal obliques and transverse abdominis continue to wrap around to the back to join with the TLF. Specifically, these fascial layers converge into a seem at the lateral edge of the iliocostalis lumborum and the quadratus lumborum. This seem then separates again into two layers with one layer traveling superficial to the erector spinae to connect with the spinous processes of the lumbar vertebrae, while the second layer travels deep to the erector spinae and between the erectors and the quadratus lumborum (so, superficial to the QL) to connect with the transverse processes of the lumbar vertebrae. This seem is the lateral raphe. It has connections to the abdominals all the way to the rectus abdominis; it has connections to the erector spinae and QL, and it has connections to bony landmarks of the lumbar spine and even the deep lumbar multifidi muscles.

This fascial seem helps integrate and balance pushes and pulls produced by all of these structures while providing a stable support for the muscles to pull on. You want the lateral raphe to be supple and strong so that it can be a structure that supports the spine while allowing the various muscles that attach to it to communicate mechanically with each other. This mechanic communication is how the myofascial knows where they are in space compared to their functional partners.

Here is a video featuring palpation and giving a brief demo of techniques to affect the lateral raphe and influence low back health.

The Lateral Raphe and its Sinew Channel Relationships

The lateral raphe is a meeting point in the fascial system. This plays out also when looking at its channel relationships, particularly looking at the sinew channels/ The following jingjin meet at the lateral raphe:

- Urinary Bladder jingjin - via pull from the erector spinae

- Stomach jingjin - following the lateral branch that travels up the vastus lateralis and into the gluteus medius and minimus fascia to the TLF and LR

- Liver jingjin - via the pull from the quadratus lumborum

- Kidney jingjin - via the pull from the lumbar multifidi